The Flexible Learning for Open Education (FLOE) project (website: https://floeproject.org/) recognizes that everyone learns differently. We all experience unique barriers that inhibit our ability to lean to our full potential. FLOE provides resources that personalize the way we learn by addressing barriers to learning (FLOE, n.d.). These resources are especially relevant to digital platforms, which is important as we increasingly depend on online education programs. I am very impressed with the variety of learning accommodations suggested on the FLOE website, along with the information about personalized learning covered in the FLOE handbook. I have worked as an instructor in both the education and healthcare field and I can see myself applying the learning accommodations suggested by FLOE in both contexts. I also appreciate that FLOE is an Open Educational Resource (OER), as it is free and available to all people to use and benefit from.

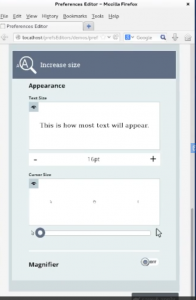

An initiative being launched by FLOE, I believe would be quite useful for all learners would be personalized digital interfaces. The FLOE project is collaborating with the Global Public Inclusive Infrastructure to develop Preference Editing Tools (FLOE, n.d.). These tools would allow individuals to declare and store their personal preferences for a variety of digital platforms (FLOE, n.d.). For instance, users would be able to enlarge font size and adjust the contrast of their desktop and browser interface (FLOE, n.d.). Personalized digital interfaces are a simple way to accommodate diverse learners with unique needs and challenges. While working at a help desk for a medical application, I got many calls from elderly users who had issues viewing text and graphics on the application website. Some issues could not be resolved with the basic alteration of visual settings on the web browser, hence I sought more efficient ways to alter the digital interface. Preference Editing Tools would have been very useful in that case and I believe they would be of great use, once launched.

Preview of Preference Editor interface:

An idea from the FLOE handbook that stood out to me was that “Some learners are more constrained than others and are therefore less able to adapt to the learning experience or environment offered; for this reason the learning environment or experience must be more flexible” (FLOE, n.d.). Reflecting on my experience as a high school tutor, this is true. Students should not be viewed as a homogeneous group. Each learner has their own unique needs and challenges. I believe instructors should do their best to present students who face barriers (such as learning disabilities) with the appropriate support they need to succeed. Technology can be extremely helpful in this case. The student I tutored had dyslexia and struggled with writing and forming sentences. His teachers had provided him the option to use the Dragon software, which transcribes speech to text. This gradually helped develop his writing skills. Furthermore, FLOE’s idea of inclusivity can be applied to this experience. FLOE states that inclusivity is to provide the end user with enough tools and features, so that they can chose which one fits their requirements in the given context (FLOE, n.d.). Students of all ages should be provided different learning accommodations from a young age, so that they can develop an understanding of which one suits their learning style the best.

Here is a short video explaining the benefits of the Dragon software, which is commonly used to transcribe speech to text:

One concept in the FLOE handbook I am having difficulty understanding is virtual cycles- specifically how altering a factor in one system can induce a reaction in another system. FLOE explains this with the example of how changing the education system in one country can impact the world economy (FLOE, n.d.). I do not understand how minor changes (such as those in education systems) could have such adverse effects. I would believe a combination of factors would contribute to larger changes; however, this is not explained in the handbook. Another idea that puzzles me is how personal discovery can be conducted for children (under the age of 10). I would believe young children may struggle expressing themselves and understanding their needs and challenges. In that case, teachers may recommend ways of interacting or learning, according to their own assumptions or medical diagnoses. However, according to the handbook, “this limits the user’s choices and makes no space for the unexpected or for variations and nuances” (FLOE, n.d.).

I have one question about Universal Design, specifically in the context of self awareness and personal learning needs:

What are some ways individuals who do not fully understand their learning challenges and barriers, increase their self awareness? Are their resources on the web that can guide individuals through the process of personal discovery?

References:

Inclusive Learning Design Handbook from OCAD University. https://via.hypothes.is/https:/handbook.floeproject.org/

Flexible learning for open education (FLOE) Project website. https://floeproject.org/